The Death Blow and a Lifeline for SMEs

Industry leaders from organizations like PCCI, AFFI, PRA and PFA have expressed fears of the deepening impact on many of their businesses.

June 10, 2020

The Real COVID Lifeline for SMEs

W+B’s internal research arm initiated polling of more than 200 SME’s and as expected most of them are grappling with tremendous uncertainty about their future.

June 17, 2020

Thousands of SMEs on the Verge of Collapse

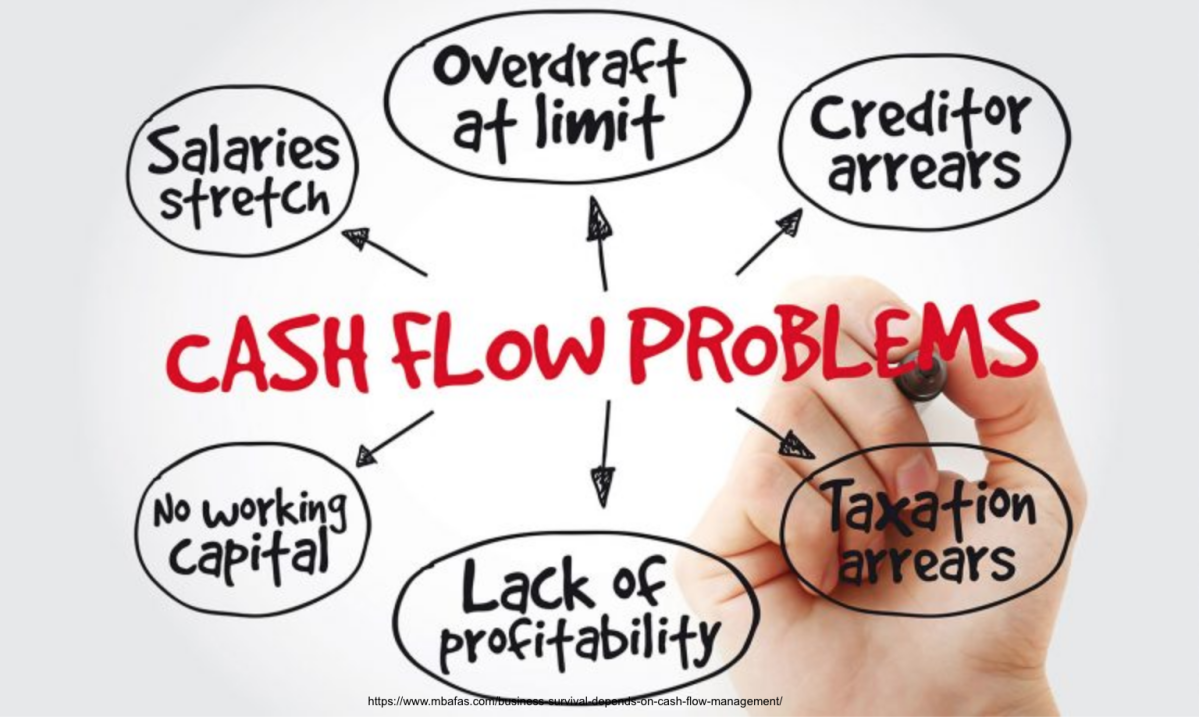

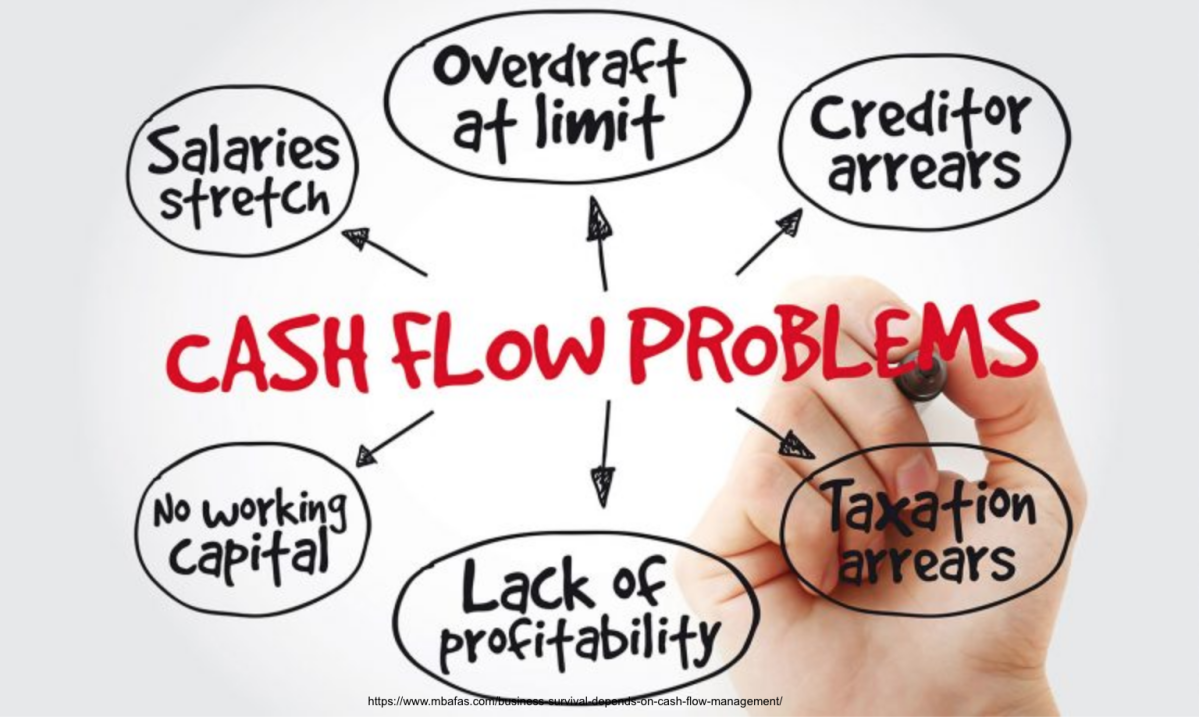

A recent study of 200 SMEs conducted in March by my consulting firm, W+B Group showed that 60 percent of the companies have seen their income drop by more than 50 percent; another 25 percent reported a 30 percent to 40 percent drop.

June 02, 2020

P140 B COVID Bailout Fund Urgently Needed Not P1B

I am urgently proposing a new round of financial bailouts dedicated to MSMEs in the amount of P140 billion. The fund will provide a lifeline to more than 200,000 SMEs so they can manage their cash flow and at the same time retain employees.

June 23, 2020

SMEs Appeal to Congress: Support Us or We die!

With the COVID-19 lifeline fund amounting to P140 billion, efforts must be done to save thousands of SMEs. An economic lifeline devoid of politics nor fear of a credit rating downgrade, focused on rescuing businesses and saving millions of lives.

June 29, 2020

Business Plan

It is a document that highlights a specific plan on how to run the company, the goals that the organization must achieve, and the necessary financial capability and strategy required and employed to meet the aforementioned objectives.

July 02, 2020

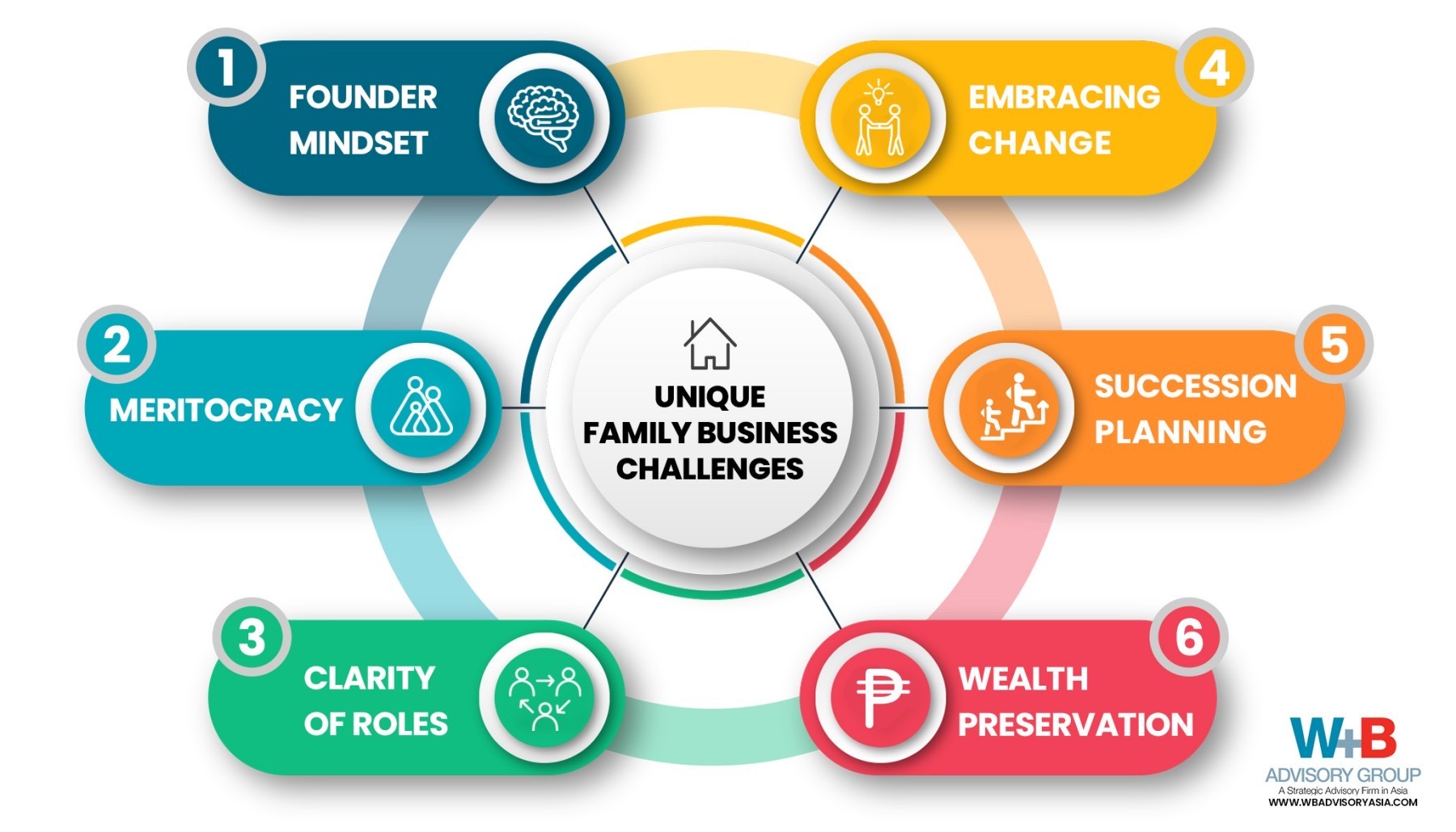

Family Business under the Threat of COVID-19

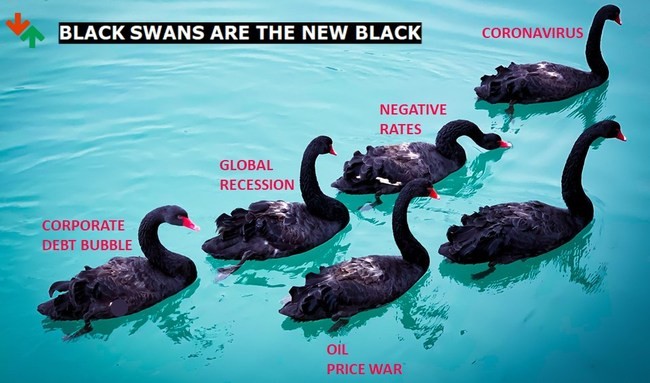

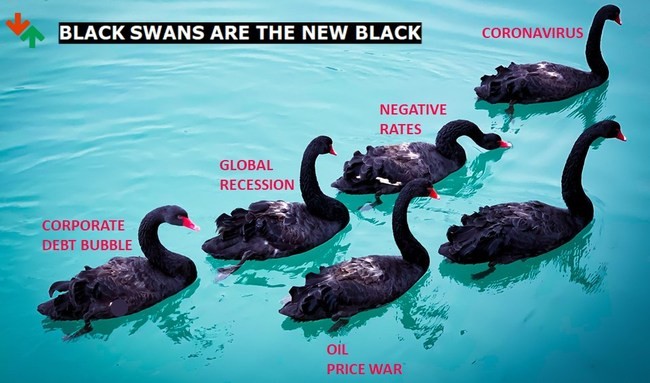

Failure to react properly to change can be an outgrowth of the firm’s history of past successes.

July 08, 2020

The Rights of Business Owners in the time of Corona

Facing imminent bankruptcy, business owners on the other hand have found themselves in a precarious situation as well. Most businesses have stopped paying wages for furloughed staff.

July 27, 2020

The Philippines and Vietnam: (Mis)Handling COVID-19

We must also acknowledge that the Philippines has taken the top spot from Indonesia as having the most number of infections in Southeast Asia. A grim reminder that the country has a long way to go before any talk of an economic recovery.

August 10, 2020

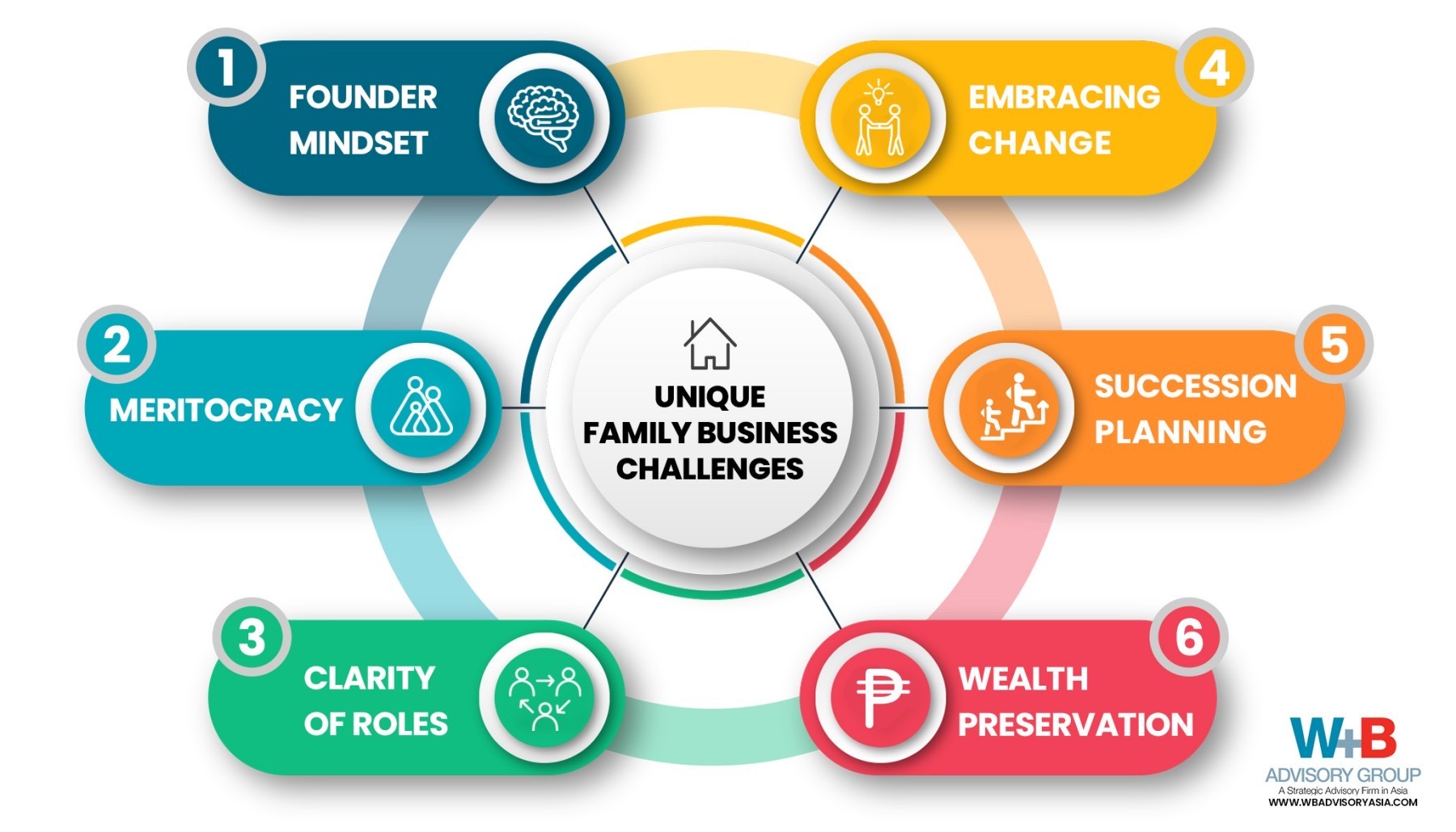

Family Business Governance — Important Then And Now

Whether in quiet times or in the midst of a crisis, Family Governance will always be crucial in creating a lasting legacy.

August 18, 2020

The Philippines and Vietnam: (Mis)Handling COVID-19 Last Part

According to an International Monetary Fund (IMF) report, "after China officially reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) several cases of an unusual pneumonia on December 31, 2019, Vietnam finalized a health risk assessment.

August 18, 2020

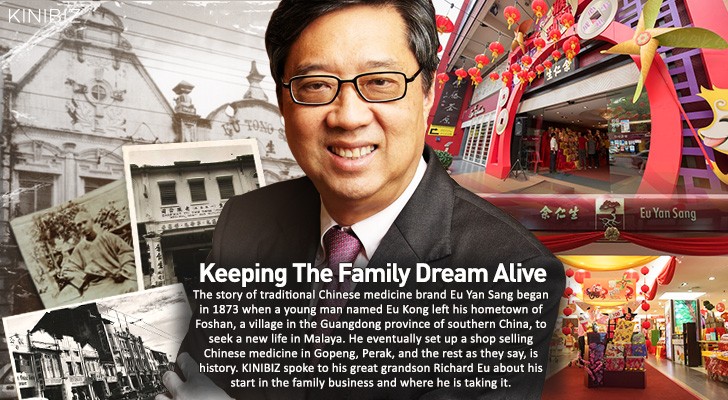

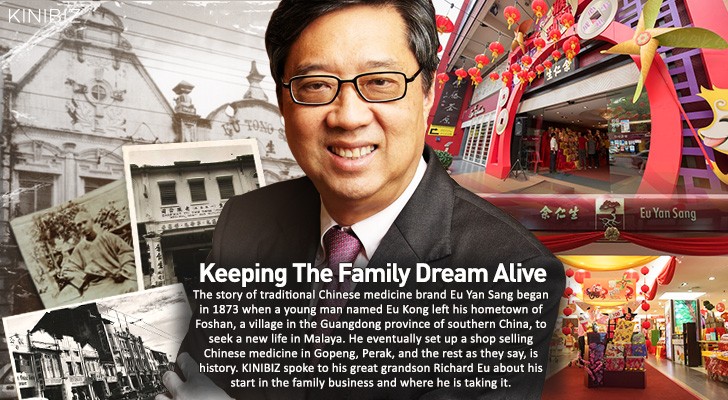

Richard Eu’s Riveting Story of his 141 Year Old Family Enterprise

“Every generation, you’ve got to think what you want to do with the family business. Is your business the right business for the future?"

August 24, 2020

SUCCESSION IS A FOUNDER’S LASTING VALUE

Succession Planning can make or break a family enterprise, “All companies are subject to risks, but family companies, because of their very nature, can more easily succumb to a series of mistakes.

September 02, 2020

When Succession Ends in Tragedy

for many founders that I have dealt with, many of them find it hard to come to terms with their own mortality. They continue to struggle and recognize the time when they feel they are no longer the best person to run the company.

September 08, 2020

Why Founders Refuse to Give Up Control?

When nepotism exerts a negative influence, and when a company is run more to honor a family tradition than for its own needs and purposes, there is likely to be trouble.

September 14, 2020

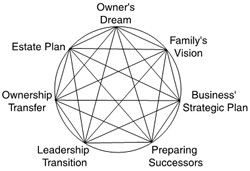

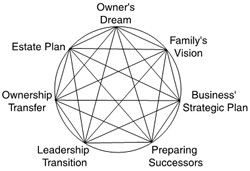

A Powerful Generational Succession Model

Unsurprisingly, most of those that inquired were curious about a powerful succession model that I have been using in my governance work in Asia for the last 7 years.

September 22, 2020

A Powerful Generational Succession Model Part 2

These two succession models are excellent, packed with authenticity and a deep understanding of the founder’s philosophy.

September 28, 2020

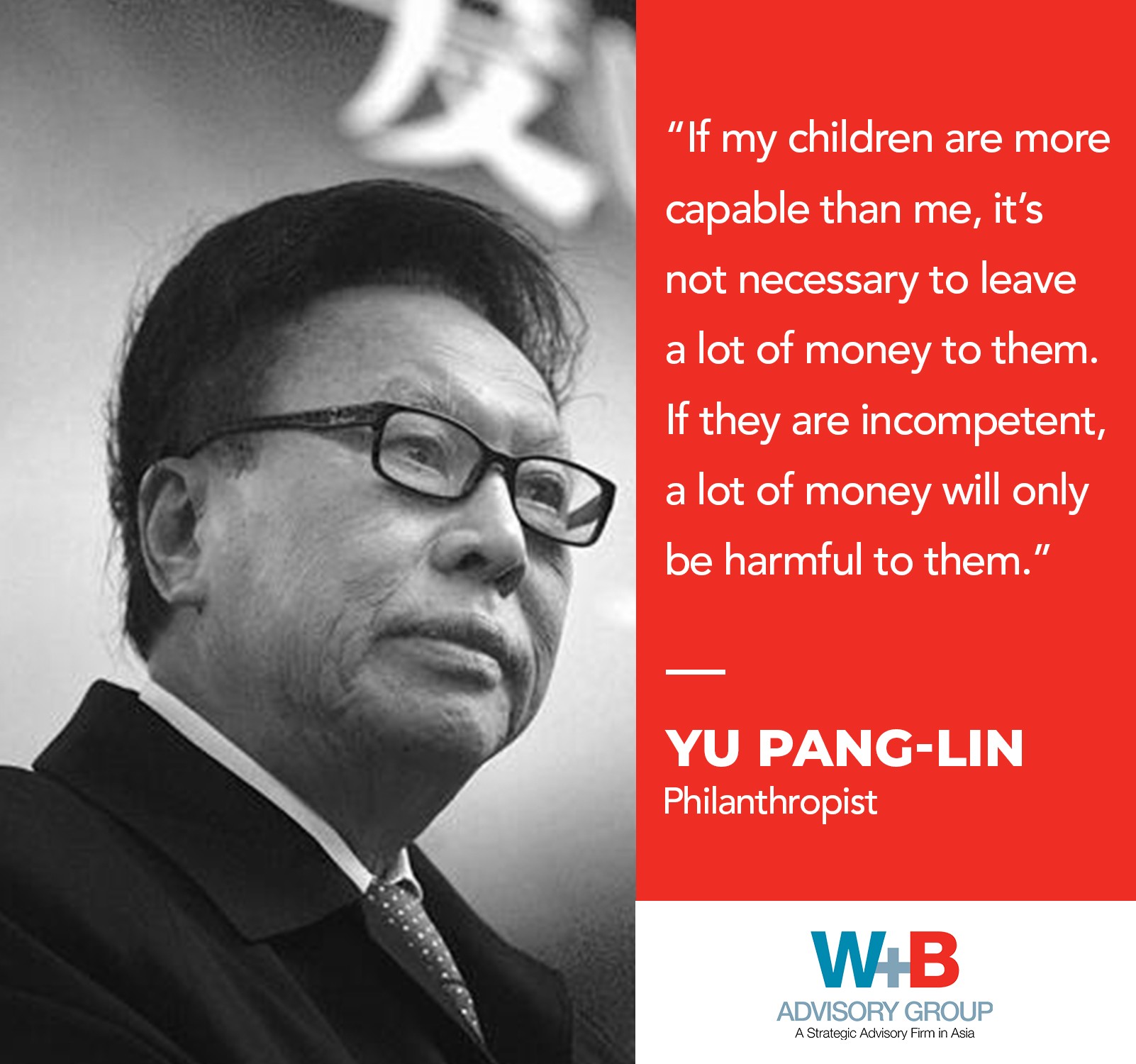

A Powerful Generational Succession Model Last Part

Clearly the worst kind of millionaire is someone who inherited the wealth from his parents and nobody could have expressed it better than the late 6th Duke of Westminster who saw his wealth as a burden he could not relinquish.

October 05, 2020

Family Conflict is Worse Than the Virus

As the adult child encroaches onto the founder’s territory and starts questioning the way the business is run, it now becomes a challenging event for the founder.

October 12, 2020

The Power of Strategic Planning

A rule of thumb is that if there's uncertainty on the horizon, then you need a strategic plan.

October 19, 2020

Strategic Planning 2021

Regardless of the size of our businesses, we are all grappling with the growing uncertainty about what lies ahead and our businesses have been severely impacted.

October 26, 2020

Strategic Planning 2021 Last Part

I can conclude that practically all of the key business leaders and executives expressed their displeasure with their current strategic planning process.

November 02, 2020

Your Purpose of Being Together

A clear collective purpose is fundamental to any family business successful transition, and those with the strongest sense of purpose are often the most successful.

November 09, 2020

Your Purpose of Being Together Part 2

It is no revelation that conflict often ensues when the founder does not define the rules of engagement amongst its active and non-active next generation offspring. The shock happens when the founder dies or becomes incapacitated.

November 16, 2020

Avoiding Family Dramas

Business survival or leaving a legacy from generation to generation requires hard work and commitment reinforced by the acquiescence of the founder or the key

November 23, 2020

Family Businesses Are Built To Last

We embraced their values of hard work 24/7, we were inspired by their stories of survival, frugality and success.

November 30, 2020

How to Manage a 141 Year Old Family Enterprise?

While other conflicted families have managed to keep themselves under the radar, they are not spared from vicious infighting.

December 07, 2020

Trust in the Family is Sacred

It takes only one aberrant family member to hurt the family and the business. It takes several ingredients to make a good stew and only one fly to spoil it.

December 14, 2020

IF YOU BUILD, THEY WILL NOT COME

How Developers Can Defy The Impact of COVID 19

December 14, 2020

From Emperor to Engagement: The Best Option

“the most successful executives are often men who have built their own companies"

December 22, 2020

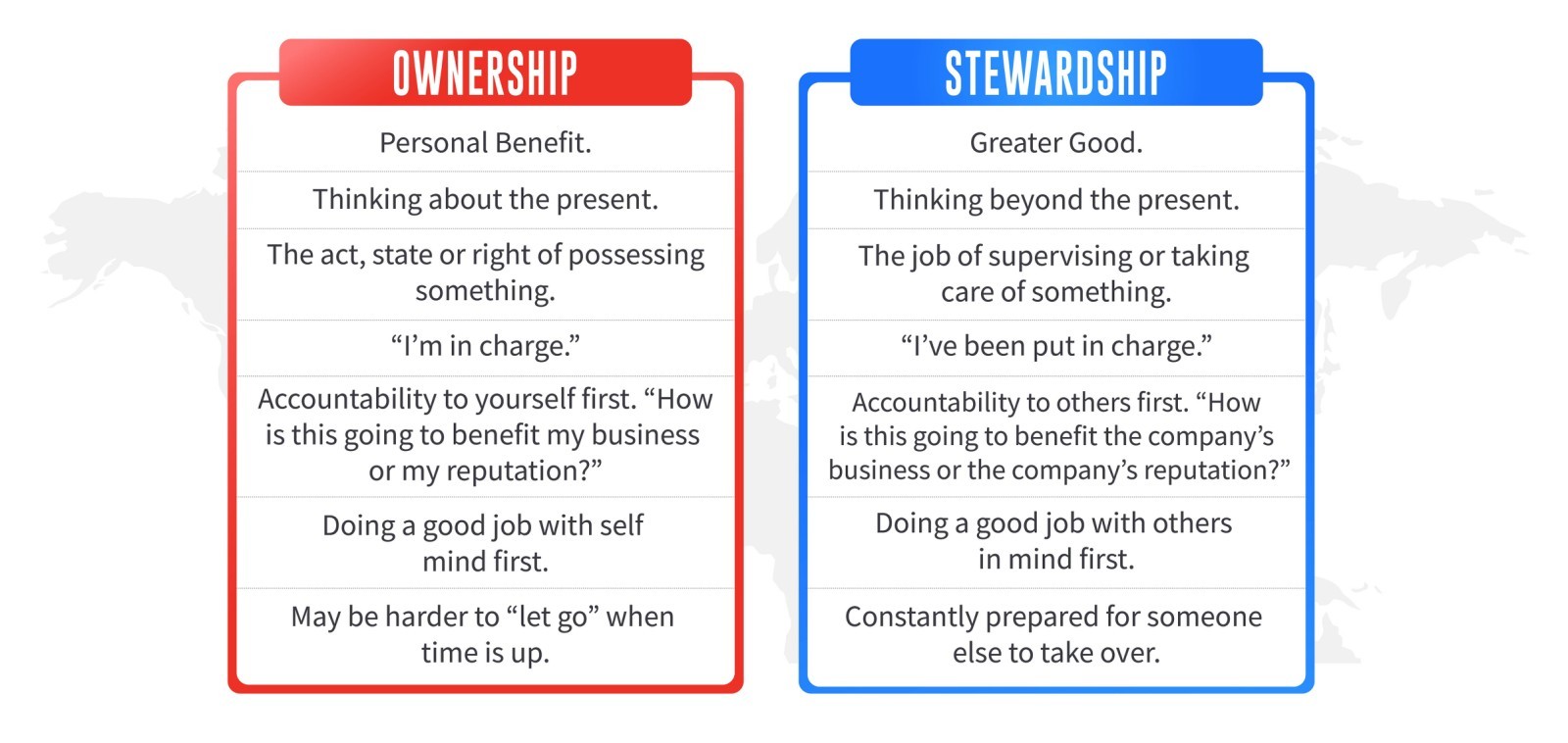

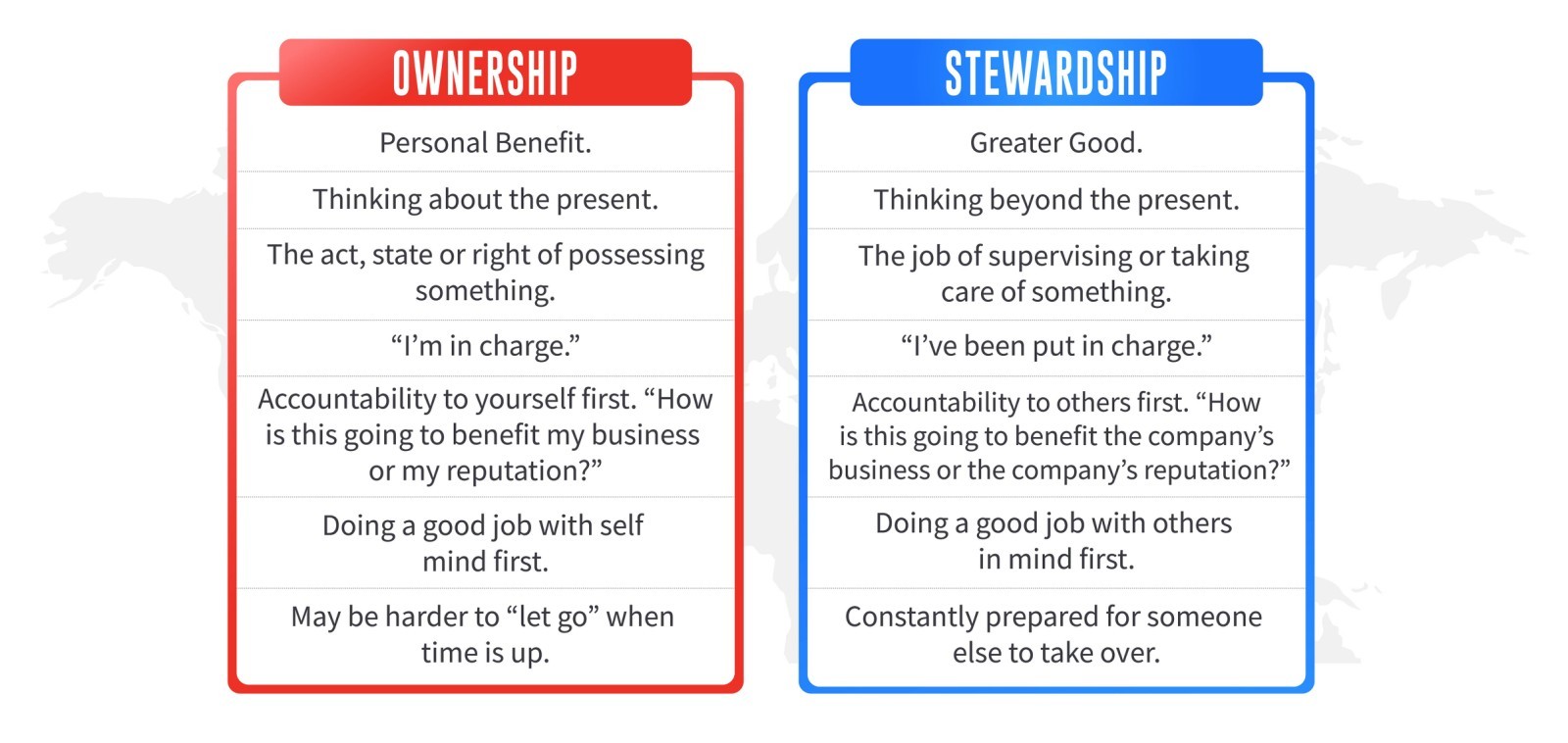

Family Business Stewardship Is a Lasting Gift

They realized that the signing of the constitution triggered a change process that carried with it the curtailment of many privileges.

December 29, 2020

Family Business Stewardship Is a Lasting Gift Part 2

Repeatedly asserting that succession is a journey that if I, as the leader, cannot embrace the process, the family business will not have stability.

January 04, 2021

The Dangers of an Ownership Mindset

It is therefore important for founders preparing the leadership transition to acknowledge that they have the potential to destroy their families through poorly planned and unclear succession processes.

January 11, 2021

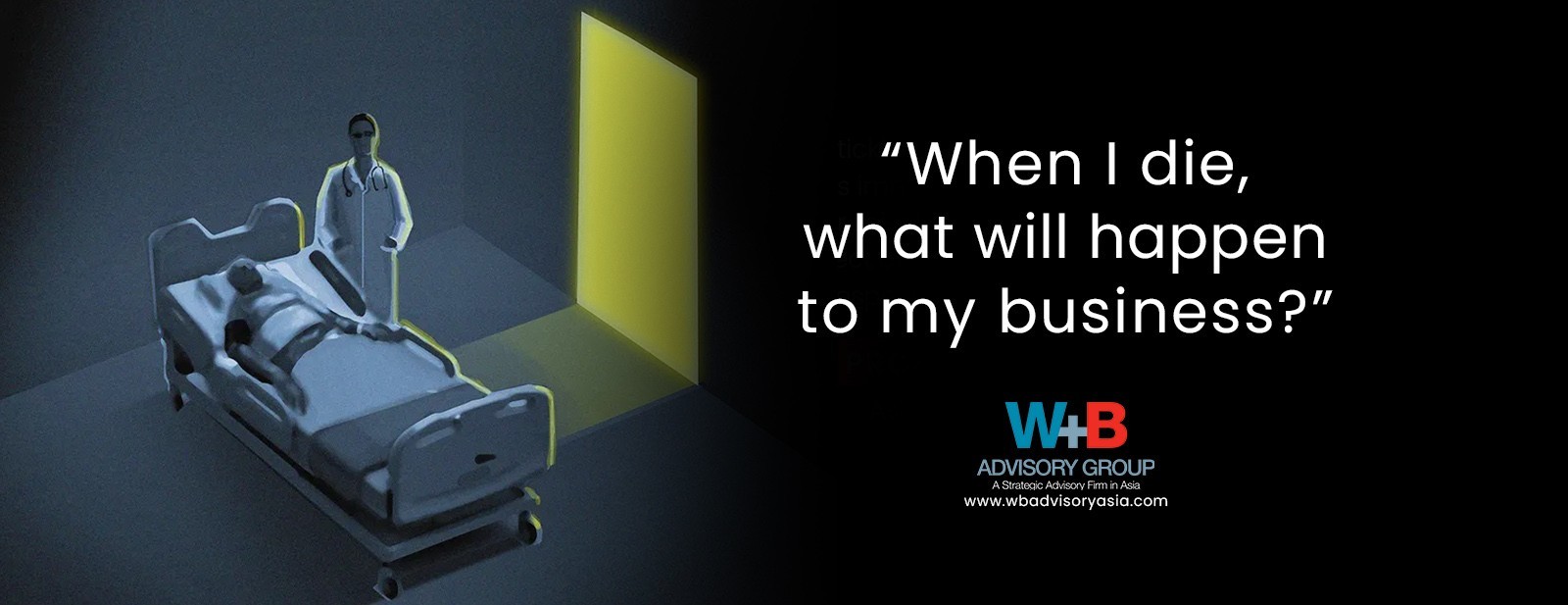

The Succession Curse

It was all talk but no action. In his 60’s and still very much in control, he unexpectedly died following a heart attack at age 64.

January 18, 2021

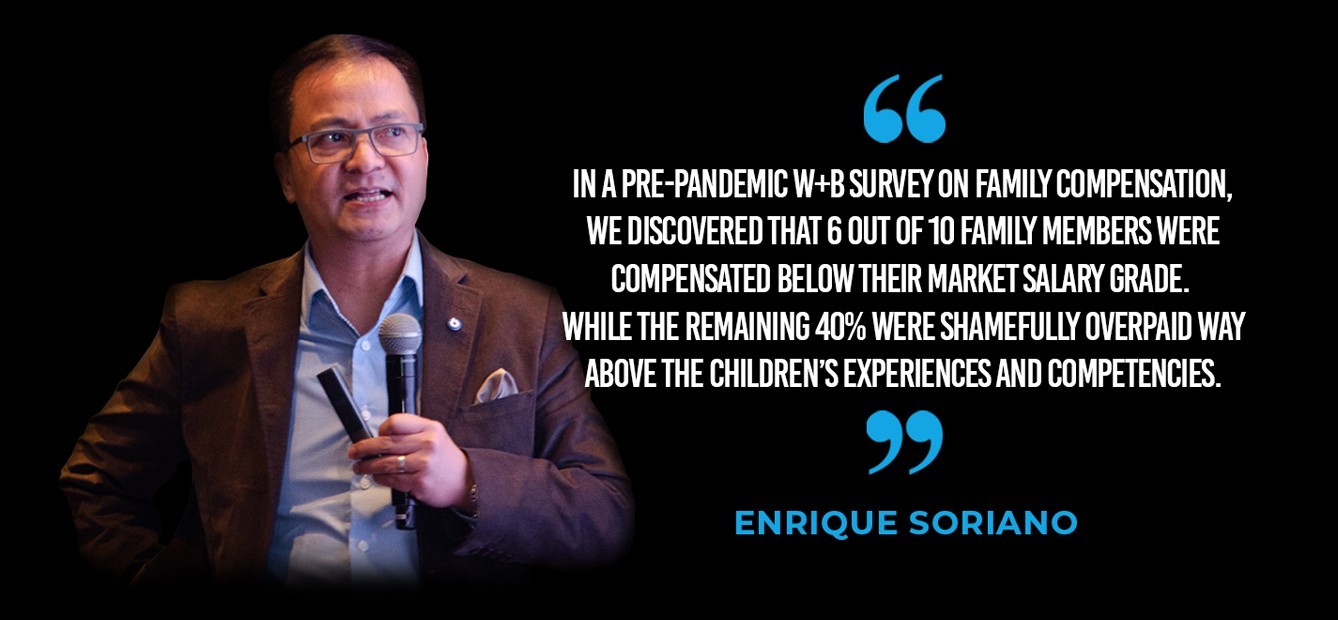

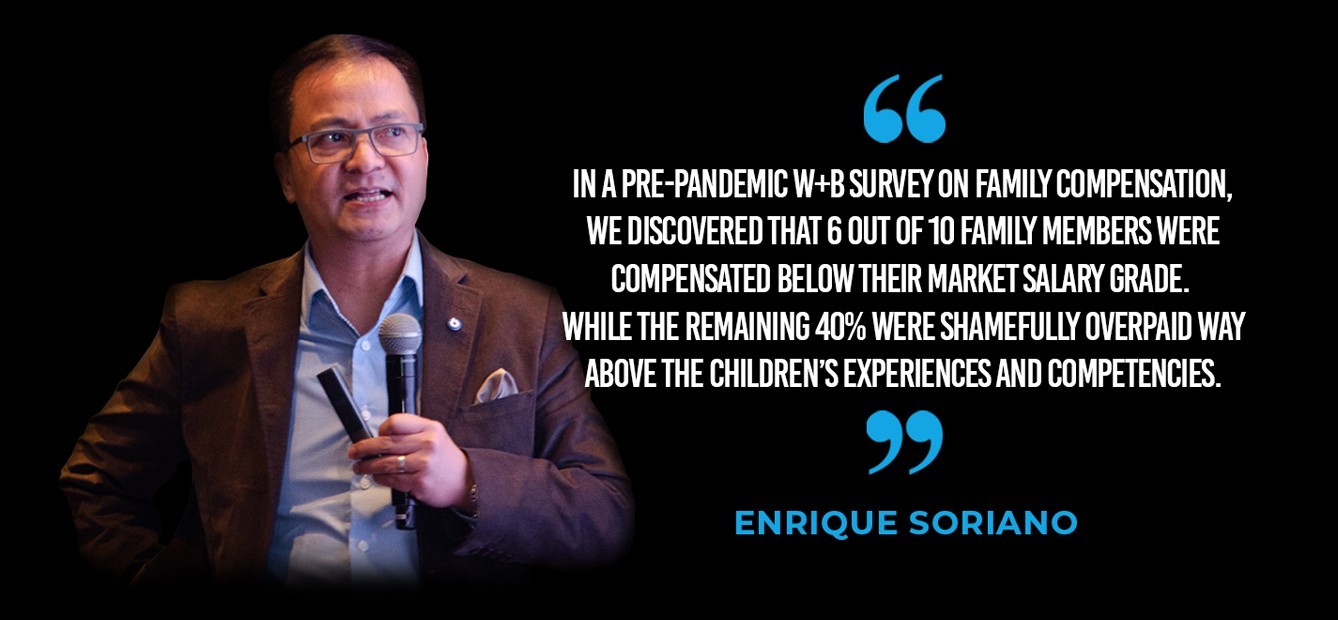

Are your Children Overpaid or Underpaid?

By pursuing a family system of compensating relatives, unbeknownst to him, the founder or business leader has started to cultivate a culture of entitlement.

January 25, 2021

What if you died tonight?

If you planned the leadership and ownership transition, I congratulate you. In your memorial service, you will be remembered fondly.

January 27, 2021

I Hope Your First Deal is a Loser

“I hope your first deal is a loser, otherwise you’ll think you’re a lot smarter than you are.”

January 27, 2021

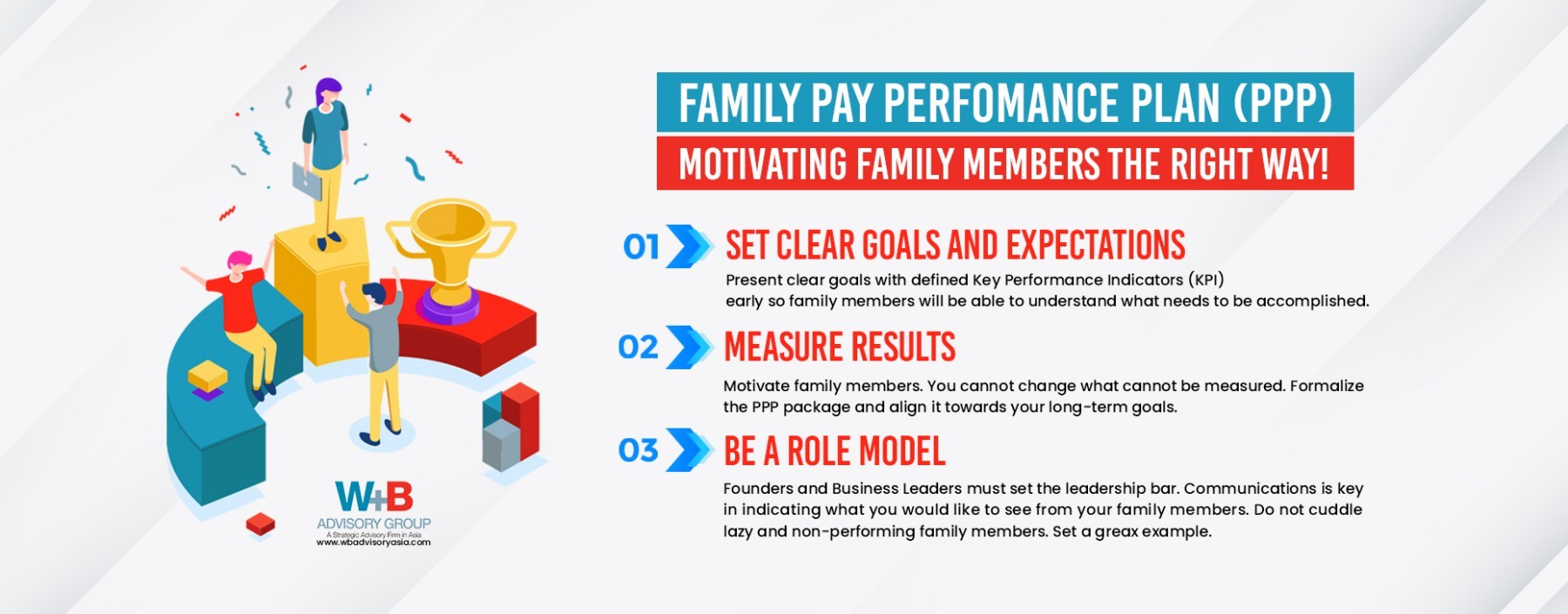

Are you Compensating Your Children the Right Way? Part 2

“Family Enterprises: The Essentials” author Peter Leach remarked in his book, “In the case of siblings, for example, fairness is generally taken to mean that resources be allocated equally.

February 09, 2021

Overpaying Family Members is Dangerous

Larry’s wrong notion of compensating family members is common among founders and business leaders.

February 23, 2021

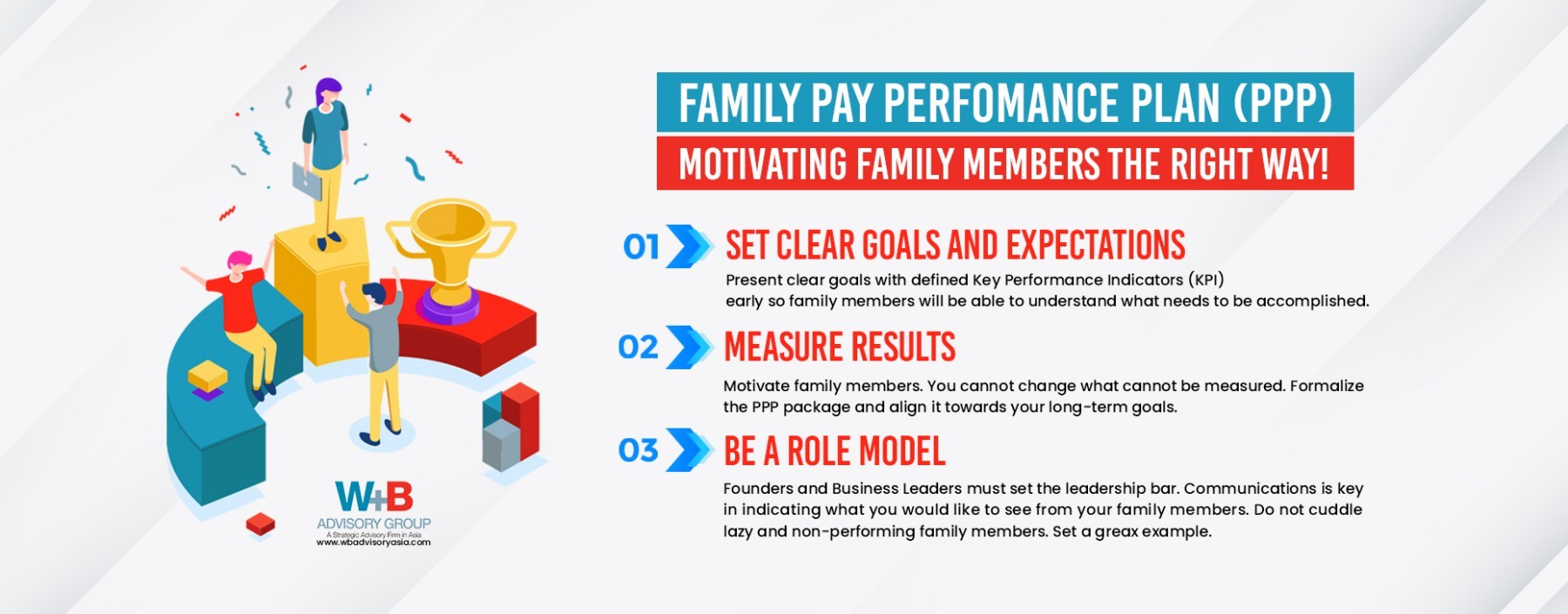

The Family Pay Performance Plan (PPP)

I was once asked by a founder why I was so adamant in pushing for a formal PPP in my governance intervention and my answer was straightforward: “It is the right thing to do!

March 02, 2021

The Family Business in a Post-Pandemic Market

One founder asked me what priorities can business owners initiate to keep the family united and prepare the enterprise for the reopening of the economy.

March 10, 2021

The Devastating Impact of Bad Leadership

You can get away with a great deal when times are good, but a major slump turns many minor issues into major problems. Good times may cover many sins, but bad times uncover many weaknesses.

March 16, 2021

Symptoms of Failed Leadership Part 2

After the first year, they start talking about restructuring, and if repayment is still in limbo by the end of this year, your friendly banker will now say, “We are going after your assets.”

March 23, 2021

The Root Cause of Failed Leadership

For starters, let me quote Albert Einstein when he said, “The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting different results.”

March 29, 2021

Life Is Fragile

In this year full of sacrifices, giving up would be a choice to relinquish hope and to dishonor all that we have been through.

April 06, 2021

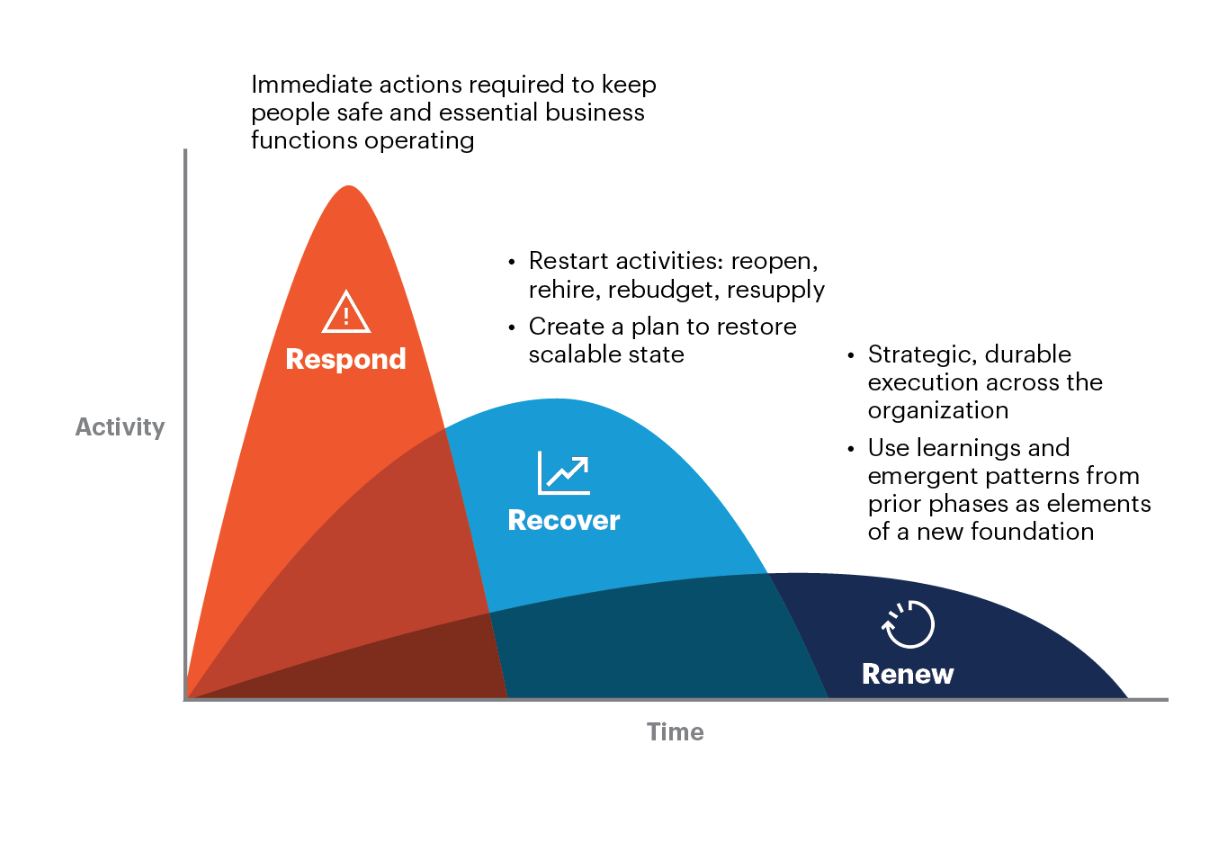

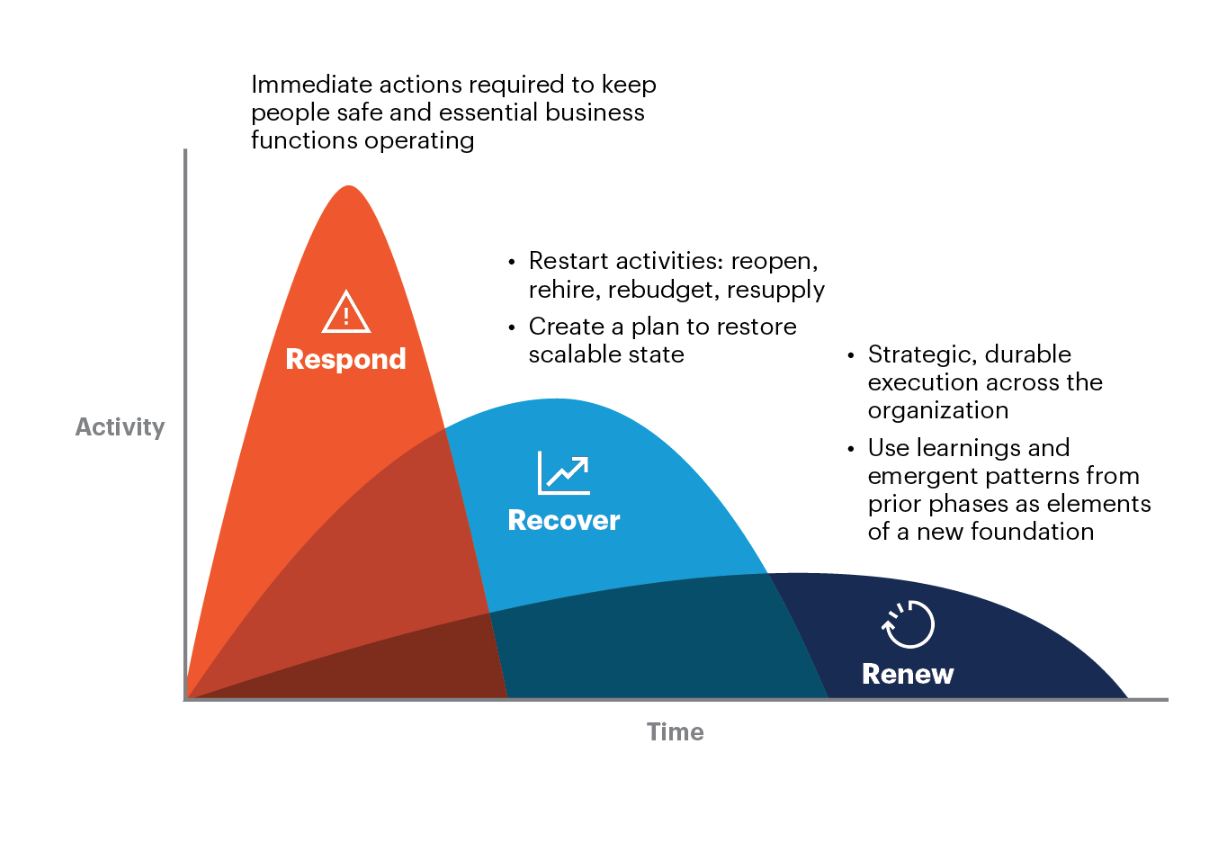

A Disruption-Ready Culture

Planning and bracing for a post-vaccine recovery is important. The art of dealing with this pandemic is keeping the business afloat long enough for the economy to kickstart and recover.

April 13, 2021

Building a Disruption-ready Culture Part 2

"Rather than continue to do everything ourselves, we decided to bring in outside experts to manage the company. Novices can only run a business for so long before its operations become too large and complex for them to handle.”

April 20, 2021

DEATH BY COVID-19

My biggest fear is what will happen to Rod’s business. Did he prepare a transition plan? Are arrangements in place to cover this eventuality and does every member of the family know about these plans?

April 27, 2021

Death By COVID-19 Part 2

Founders and key business leaders should never think they are Supermen. The truth is, they will soon die. No ifs or buts. It is just a matter of time.

May 06, 2021

A Sudden, Complicated COVID-19 Death

As your face is pressed up against the casket glass, you see a parade of people mostly family members and employees crying softly, helpless, numbed, their heads bowed, uncertain of what lies ahead as the business is in limbo.

May 11, 2021

A Sudden, Complicated COVID-19 Death! Part 2

The majority of family-business owners put off the steps necessary to plan ahead. But if you want your family to honor your last wishes, they must know what your wishes are.

May 18, 2021

Procrastination is the Worst Enemy of Succession

Without a decent succession plan, your sudden death could see your loved ones in a sea of confusion where they are left to figure a way out of the difficult situation you left them in on their own.

May 25, 2021

Change in Founder Mindset

It does not matter if an owner doubts the next generation’s commitment to the family business.

June 01, 2021

He knew this day would come

George needed his children to prove themselves first as a part of a carefully planned transition set to prepare his family, his business, and his people up to the very specific end.

June 09, 2021

He knew this day would come Last Part

As a fitting tribute to George’s beautiful succession story, I am sharing a quote from a Chinese proverb, “When the winds of change blow, some people build walls and others build windmills.” It is time for founders to choose well.

June 16, 2021

A Toxic Father-Son Relationship

I longed for parental love, but instead, he showered me and my siblings with material love. When I joined the business, it was like a hellhole and I felt miserable.

June 22, 2021

"Human Resources are priceless."

How did the founder in the early stages of CP’s existence cultivate a mindset that recognized human resources as a key business driver for corporate transformation, organizational success, and sustainable growth?

June 29, 2021

Your legacy is on the line

“Longevity is not a guarantee, it’s something that you really have to fight for and every generation has to do it.” - Willem Van Eeghen

July 05, 2021

Honoring a Founder’s Legacy

Deloitte partner Alexandra Sharpe highlighted that “the most successful family enterprises around the world manage to unite the constituent individuals, family and business and coalesce them around a common sense of purpose.

July 13, 2021

Hidden cracks in the Family Business

Founders who are in their late 60’s have agreed that each child will be given 30 percent of the stock while the remaining 10% is retained by them.

July 20, 2021

Hidden cracks in the Family Business Part 2

Business owners, aka absentee parents, tend to shower their offspring with material love to compensate for the lack of parental love and lessen their own guilt, which often exacerbates the brewing rivalry among siblings.

July 27, 2021

A Terminally Ill Founder

On top of providing jobs, he was also recognized for his many philanthropic contributions benefitting many schools and medical institutions. The only problem? He was terminally ill.

August 03, 2021

A Terminally Ill Founder Part 2

I reiterated to everyone, especially to the children that as they embark on this succession journey, they must also walk it faithfully. T

August 10, 2021

A Founder’s Harmful Side

They remain at the center of all major decisions and they tend to have little trust in others. Unless a transformation to a more professional structure happens before the founder dies, these types of founder-centric firms do not always survive.

August 17, 2021

I'm the company and the company is me!

In family businesses the world over, the most pervasive conflict has to do with succession because great visionaries and founders have been useless at succession planning.

August 24, 2021

When Founders Play With Fire

When you sense these dangers in your family business, do something now. These are worrying signs that the company may be heading towards a turbulent phase.

August 31, 2021

We have met the enemy, and he is us

When you put all these issues together, there is really one culprit that creates most of the problems afflicting family owning businesses today, and without a doubt, that is you.

September 07, 2021

Is the Chinese Way in Peril?

In many cases, it almost always starts when a key business leader dies. The death of a founder can disrupt the very foundations of the business and the institutions where the lives of employees and the many stakeholders depend on.

September 22, 2021

Is the Chinese Succession Model In Peril? Part 2

One of the critical issues worth mentioning is the eldest son succession system which has been in existence in China for more than a thousand years.

September 28, 2021

Is your Organization Suffering from "Founderitis"?

This type of behavior is called the “founder’s syndrome” or “founderitis,” which commonly afflicts many business owners struggling between sharing major decisions and holding on to power.

October 05, 2021

Is your Organization Suffering from Founderitis? Part 2

When decisions revolve around him and he is reluctant to pursue change, the likelihood that pressure will build up from many dimensions—the family, the business, and his own mortality—escalates.

October 12, 2021

Is your Organization Suffering From Founderitis? Part 3

When change becomes inevitable because of age and health issues, founders will have a hard time adjusting to the new reality.

October 19, 2021

Is your Organization Suffering From Founderitis? Last Part

The drive to create and lead an organization. The surprising thing is that trying to maximize one imperils the achievement of the other.

October 26, 2021

Trust Your Children To Do a Good Job

My father believed that for us to appreciate the different nuances of our businesses, we had to start from the bottom and get our hands dirty. - Lance Gokongwei, President and CEO of JG Summit Group

November 03, 2021

Start Succession Planning Now!

My advice to founders is to go for early succession planning. Three years is tight, five years in advance is good, but ten years is much better.

November 10, 2021

Succession Is a Make or Break Event

With procrastination prevailing over succession, the chances of the business heading towards the path of self-destruction are high.

November 16, 2021

Founder’s Unfounded Fear

Why do the majority of these owners procrastinate and set aside the steps necessary to plan ahead? Why are they so emotionally uncomfortable in embracing the succession roadmap?

November 23, 2021

Papa Will Never Give Up Control

Death is not an easy subject to talk about, nor is retirement. But it is a subject that needs to be addressed by the family.

December 02, 2021

The Right Succession Model

Despite all these handover constraints, overall, I was delighted as this succession journey took more than five years to finally realize its significance.

December 07, 2021

Founder’s Dream: Preserving Wealth and Legacy

Having an undefined, unclear, founder-centric culture mixed with confused, entitled family members is a recipe for disaster.

December 15, 2021

Founder’s Dream: Preserving Wealth, Unity and Legacy Part 2

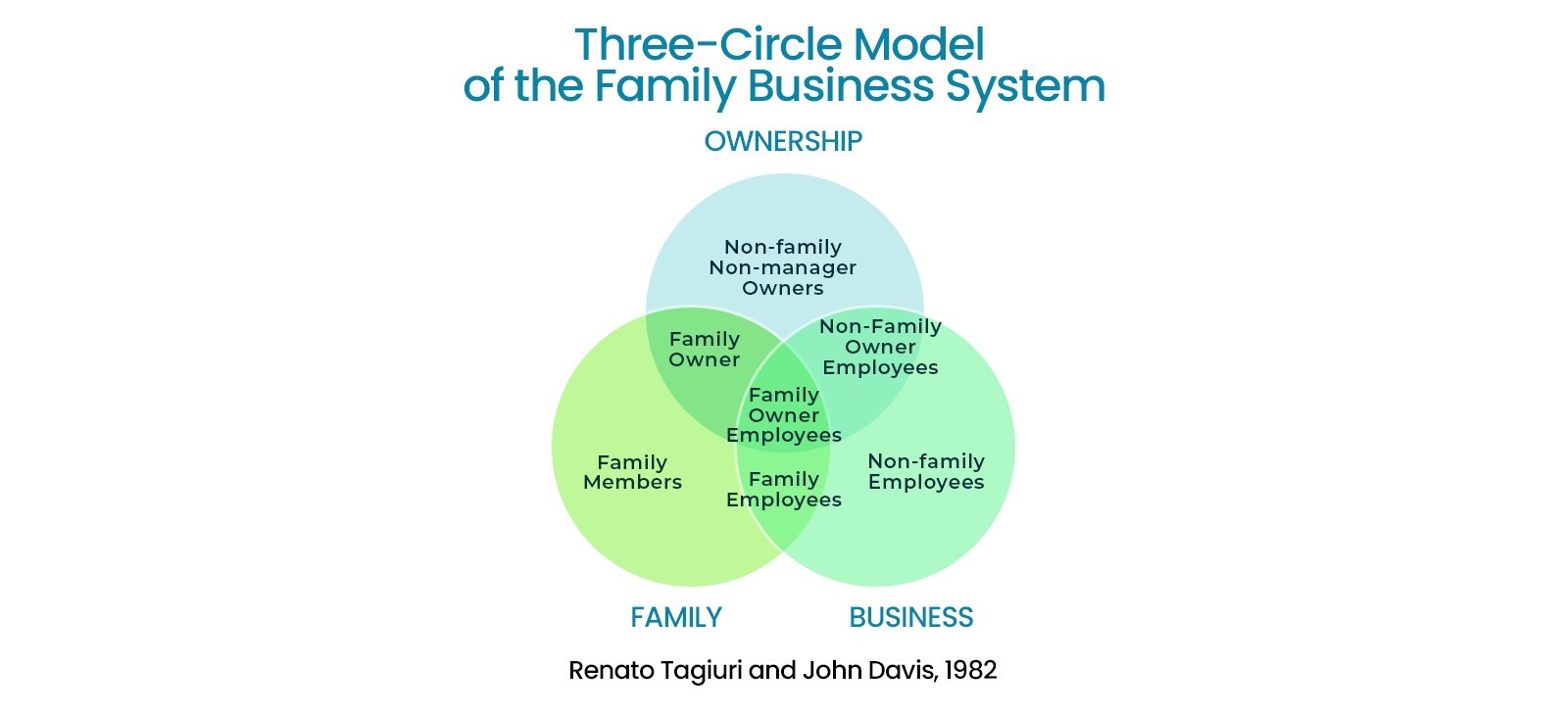

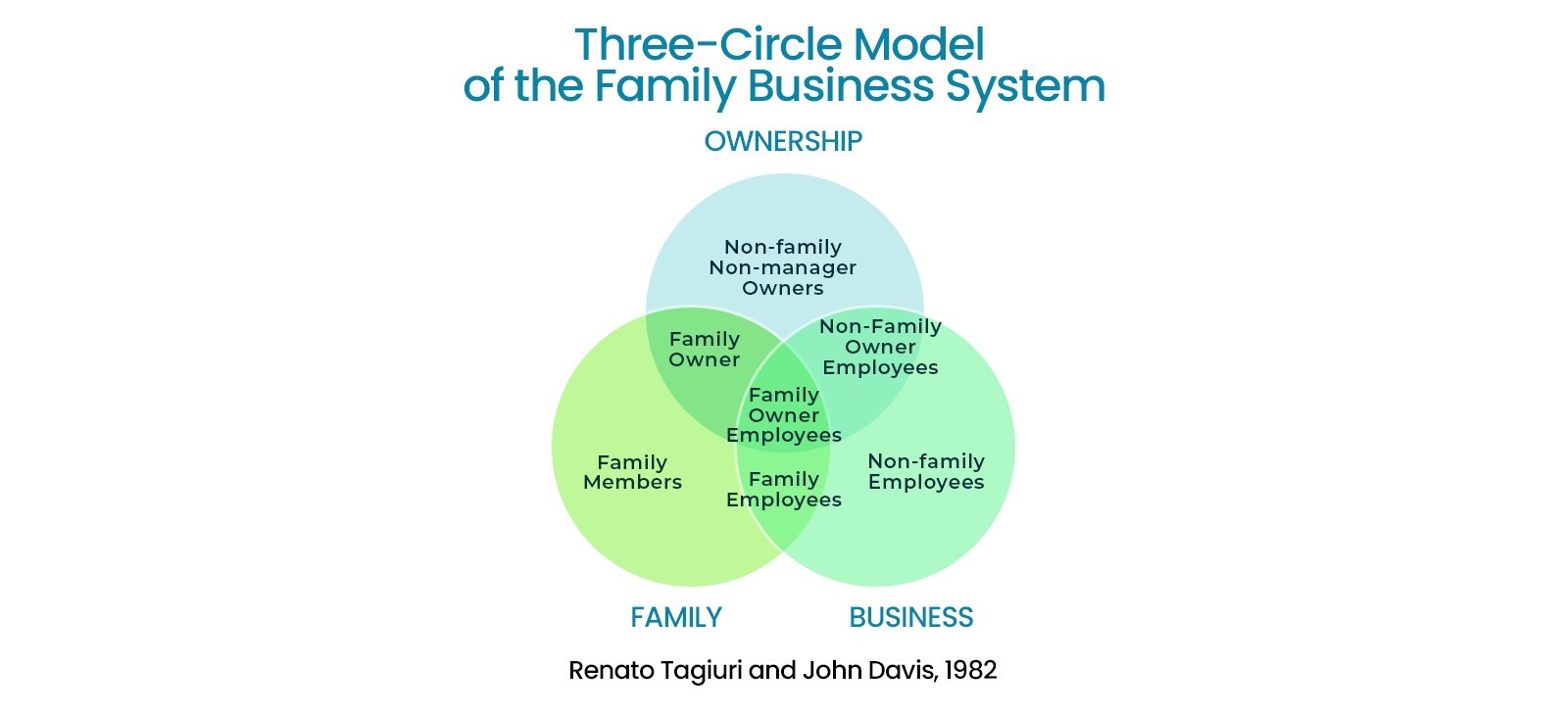

The family business model is a unique system fraught with emotions. It also has naturally different goals. Family members may share the same values but may have different visions of where they want the business to head.

December 22, 2021

‘Tis the Season to Repair Old Wounds

For families with a history of conflict, it is time to reflect if you will continue to be haunted by ongoing conflicts or look at this holiday season of love and forgiveness as an opportunity to repair broken relationships.

December 27, 2021

The Family Must Commit To Reconciliation

From a family governance perspective, any reconciliation process between acrimonious family members should be initiated and supported by the family.

January 04, 2022

How Do You Say Sorry to Someone Who Has Died?

Nobody wins in any emotionally charged, ego-centered, finger-pointing discussion. It is always a defeat for all parties, the entire family included, and it severely affects relationships that can translate to harmful and sometimes destructive behavior.

January 12, 2022

A Business Managed With Emotions

With the presence of additional family members (including their spouses and children), when a family business transitions and moves along its generational timeline, you can expect an explosion of personal interests clouding business judgments.

January 18, 2022

“The problem with this family is the lack of communication!”

PWC’s Amin Nasser highlights in his article, “The two greatest threats to the successful continuity of family businesses are conflict and succession. And these two critical elements are caused by a failure to communicate!”

January 24, 2022

The Dangers of Poor Communication

When you fuse these business-related conflicts with traumatic childhood experiences, the hostility spills over to real overt conflicts such as threats, intimidation, and even sabotage.

February 02, 2022

Is Family Compensation a Forbidden Topic?

It is clear that many founders instinctively based their compensation policy on the notion of what is best for the family rather than on what is best for the business. This old family compensation model must stop.

February 08, 2022

A Fair Compensation Plan For Active Family Members

By pursuing a family system (family first instead of business first) of compensating relatives that is flawed, the business leader has started a culture of entitlement.

February 15, 2022

A Fair Compensation Plan For Active Family Members Part 2

There is no longer any justification for the parent/owner to give low salaries based on the rationale that the children will eventually take over the business.

February 22, 2022

A Fair Compensation Plan For Active Family Members Part 3

Why do I espouse these ground rules? Fundamentally, the compensation conflict stems from the fact that the role of each family member was never clearly defined from the very beginning.

March 02, 2022

A Fair Compensation Plan For Active Family Members: Last Part

When the pay structure of family members remains unclear, undefined, and not explained thoroughly, the emotional element can manifest in the form of jealousy, rivalry, and conflict.

March 08, 2022

Why Do So Many Family Businesses Fail?

There is a powerful value that serves as a beacon of light for family firms, and it is a clear and collective purpose that everybody must share.

March 15, 2022

A Powerful Sense of Purpose Can Withstand Generational Challenges

I can conclusively say that the lack of communication, the absence of a shared purpose, and the false belief that family unity is paramount are the major reasons family-owned businesses do not last two or three generations.

March 22, 2022

The Lack of Meaning and Purpose is a death sentence for family firms

Is it purely because of blood and money? Collectively, are family members looking at the horizon or seeing themselves out of the business to enjoy daddy's money

March 29, 2022

Breaking a Promise To Your children

I still want to take the lead, but I also want to empower my children to make major decisions. Is it possible to do both — to step back but still be involved without overriding their decision? What if they commit major mistakes?

April 05, 2022

The Family Suffers When There is No Will to Change

Reinforcing a founder's unfounded fears such as fear of the unknown, of losing power, of failure of the next generation, and of doing nothing when he decides to step back is their paranoia of what they incessantly hear from their friends.

April 13, 2022

The Family Suffers When There is No Will to Change Part 2

Mixing family and business issues is like speeding downhill on a rain-soaked, dangerous zig-zag road using a car with defective brake pads. Having family issues in the business is always full of emotions and contains subjective decision-making.

April 20, 2022

Planning, Empowering and Committing (The PEC Way)

The PEC program I mentioned is not about forcing leaders to retire and leave the business entirely. I do not subscribe to the idea of overnight and abrupt decision to let go of power. It goes against the grain of governance.

April 27, 2022

The Inconvenient Truth

I was asked how I differentiate a healthy family enterprise from an unhealthy one. My straightforward answer was how each embraces change as it unequivocally translates governance and succession, shared purpose and alignment of vision and values.

May 04, 2022

The Inconvenient Truth Part 2

Jack recounted the day he suddenly clutched his chest after feeling tightness that radiated to the base of his neck, jaw, and left arm, recalling how if not for the quick action of his staff, he would have died.

May 11, 2022

Every Family Constitution Is Unique

Without any doubt, crafting a family constitution is one major step toward every founder’s dream and aspiration to ensure that his blood, sweat, and tears can perpetuate the business for generations to come.

May 18, 2022

The Dangers of DIY Governance

Many families lean towards DIY governance to either take a break from months of governance sessions, prioritize and focus on making money, consider costs, and gain the 'feeling' that the family is talking again.

May 25, 2022

The Generational Impact of a Family in Conflict

Sadly, when adult siblings take their issues into the legal forum, with inherent delays, high costs, and frustrations, irreparable damage to the family may be caused and it would be very difficult to restore trust.

May 31, 2022

Fight, Flight, or Mediate?

The final test of a committed and sincere family is how they can agree to disagree in a climate of trust, objectivity and relentless communication.

June 08, 2022

What drives people to declare war against their own flesh and blood?

Any legal drama will eventually morph into a public scandal where the courts and legal advisors will end up as the only clear winners.

June 15, 2022

What drives people to declare war against their own flesh and blood? Part 2

"Inheritance conflict doesn’t come out of nowhere; it is a continuation of long-term relationship problems that resurface upon the illness or death of a loved one.” – Estate Planning expert P. Mark Accettura.

June 21, 2022

Sibling Rivalry. Is it Personal or Business?

The founder/parent must lead the way in resolving the conflict. There is no other person in the family that can do it.

June 28, 2022

The Twin Evils Unique in Family Businesses

By its very nature, the family and business systems are so conjoined that when left on their own to feed, they can lead to frayed nerves, emotional conflict, and inevitably schism.

July 05, 2022

Parents' Letter to a Distraught Son

As parents, we are aware that it can be difficult to manage relationships in a family business context given the different roles we play and the confusion it at times creates without clear boundaries between these roles.

July 13, 2022

Parents’ Letter to their Distraught Son Part 2

Regarding the lack of open communication that's unfortunately common between parents and their children, we believe that both parties should do more to address this.

July 20, 2022

Parent’s Letter To Their Distraught Son: Integrity and Commitment

The most successful family businesses that have lasted for many generations are effective in drawing boundaries between two distinct areas – the family side and the business side.

July 27, 2022

Stop Building A Business. Start Building Your Legacy

In any governance and succession journey, every founder must realize that the greater good philosophy must and will always prevail.

August 03, 2022

Successful Succession: A Founder's Test of Greatness

Management expert Peter Drucker once said, "The final test of greatness in a founder is how well he chooses a successor and whether he can step aside and let his successor run the company."

August 09, 2022

Avoid Transforming Petty Conflict To Hatred and Hostility

“Every family business is unique and complex in its own way, so boilerplate solutions don’t always work. Still, there are common rules of engagement for handling employees who are related by blood or marriage.”

August 16, 2022

‘The trouble is, you think you have time.’

There may not be any ‘later’ for us to do the thing we decided to put off, so to amplify my advice to all family business leaders, start the journey now.

August 24, 2022

Giving the Next Generation Leader Wings

Roby, a second-generation family member, was rotated by his father among the various departments of their business.

August 31, 2022

Giving the Next Generation Leader Wings Part 2

Every founder’s dream is to watch their children grow up to become responsible adults, eventually join the business, and work as a team to ensure the business becomes successful, but, 7 of 10 family-owned businesses do not make it to the third generation.

September 07, 2022

Why Do Siblings Fight for Control and Money?

United families that are successful and less prone to conflict have these three things: (1) a unifying goal, (2) open and formal communication, (3) leaders that are smart enough to think about the next generation.

September 14, 2022

Whose Fault is it When Siblings Fight in the Business?

Almost 60% of our intervention as an ASEAN family business advisor happens to be sibling rivalry, especially among offspring that work together whose tensions are “rooted in conflict over business styles and strategies rather than family emotions.”

September 20, 2022

The Deadly Cost of Weak Governance: Business Failure and Family Conflict

Why do petty conflicts often morph into sibling rivalries? The blame falls squarely on the leader either for choosing the “Do Nothing” option or carelessly selecting an unqualified, inexperienced family consultant.

September 27, 2022

Is Your Family Qualified to have a Family Constitution?

Flawed family constitutions are usually made of completed agreements and signed documents that are never enforced, enhanced, and implemented, making them just some useless piece of paper.

October 04, 2022

The Dangers of Hiring an Inexperienced Family Consultant

Succession is daunting and challenging and will require emotional acceptance from the leader that the time has come to lead this very critical and significant milestone in the life of the enterprise.

October 12, 2022

The Non-Negotiable Qualities of an Experienced Family Consultant

As the founder/manager of a 35-year-old construction business who went through an open-heart surgery, Rey became fearful of what might have happened if he did not survive the ordeal.

October 19, 2022

The Benefits of an Experienced Family Business Consultant

A consultant’s task is to amplify a very important message: that governance, succession, family harmony, and legacy go hand in hand.

October 25, 2022

A Founder’s Spectacular Failure!

Take note: a company is only as good or bad as its leaders, so the real fault lies in those who run them.

November 02, 2022

A Founder’s Spectacular Failure! Part 2

This second article will highlight the visible symptoms of internal wrongdoing, mismanagement, and failed leadership by a very controlling founder

November 08, 2022

Spectacular Failure! Hubris, the Silent Killer of Business Last Part

Any corporate transition must be deliberate since many enterprises typically start as informal mom-and-pop businesses.

November 15, 2022

The Single Worst Mistake Business Owners Make: DOING NOTHING!

The failure of the leader to set the rules of engagement early on can inevitably spark next-generation conflict.

November 23, 2022

Entitlement Can Destroy a Family Enterprise

Without a doubt, the fault lies with the founders/parents/owners. They play a major part in cultivating entitled family members

November 29, 2022

Affluence + Influence = Entitlement: The Red Bull Scion Story

Parents/Owners/Operators must be firm and should play the part of business owners rather than parents. Mixing the two hats in a business environment is a recipe for having entitled children.

December 06, 2022

A Lifetime of Entitlement: The Red Bull Scion Story

Entitlement issues are rampant in family enterprises. It is a dangerous disease that can damage the family business.

December 14, 2022

Having Entitled Family Members Is Plain Wrong!

One thing is clear, having entitled family members is a clear and present danger.

December 20, 2022

'Someday This Business Will Be Yours'

When your children grow up believing that they will own the business no matter what they do or how they act, an entitlement mindset is conditioned at an early age.

December 29, 2022

When Blood Becomes a Birthright

For the new year, it is appropriate and timely to reinforce to one and all that raising non-entitled children (and grandchildren)

January 04, 2023

Preventing Entitlement Starts With Good Parenting

There are many ways to prevent children from becoming entitled. The most effective approach is through role modeling and communication.

January 10, 2023

Baa, Baa, Black Sheep

Tagged "black sheep" family members are indeed quite a character.

January 24, 2023

The Consequences of being an Absentee Father (Mother)

As an exasperated parent-founder once said, "It is easier to run a conglomerate with thousands of executives, but it is far more difficult managing an offspring." But why do 'black sheep' family members really exist?

January 31, 2023

Is It Fair to Divide Your Wealth Equally?

The question that begs to be answered is: “Is giving equal ownership really fair, or is fairness in the context of wealth transfer never equal?”

February 07, 2023

Giving Your Children Equal Compensation Is Wrong

Conflict is normal in family businesses, but the unresolved ones classified as excessive can ultimately create damage and instability that, when not constructively dealt with, can open a prolific source of deep-seated problems like a pandora's box.

February 15, 2023

Poorly Crafted Family Compensation Policy is Divisive

Without understanding the concept of compensation, the children may end up disillusioned, confused, frustrated, and constantly asking why their salaries are equal.

February 21, 2023

A Tale of Two Siblings Fighting a Lost Cause

Conflicts in life are unpleasant. It destroys relationships and zaps the energy of individuals and their families, so many families try to avoid conflict at all costs, which is a big mistake.

March 01, 2023

50/50 Estate Split is a Double-Edged Sword: A Parent’s Dilemma

With the businesses going full throttle, the couple became worried that if they gave the business to son B, which seemed fair to do, they would not have any means to treat son A equally, which seemed unfair to him.

March 08, 2023

50/50 Estate Split is a Double-Edged Sword Part 2

Splitting assets and shares of the family business between your children can be tricky as it puts to the test the parent owners’ fairness to everybody

March 15, 2023

50/50 Estate Split is a Double-Edged Sword Part 2

Splitting assets and shares of the family business between your children can be tricky

March 15, 2023

You Can Never Manage Your Business From The Grave

The stakes are high, the consequences of a wrong decision are devastating

March 21, 2023

Rights of the Next Generation's Spouses

As a family business grows and is passed on to the children, concerns arise regarding the rights of the next-generation family members and their spouses to own and control the company.

March 29, 2023

When Shares Are Carelessly Passed On To In-Laws

Having in-laws owning shares in a family business has challenges

April 12, 2023

How to Effectively Manage In-Laws Last Part

If you really believe that in-laws deserve to be future shareholders, it is absolutely necessary that clear policies and procedures must be in place for in-law employment, share ownership

May 17, 2023

Advantages and Disadvantages of Family Members Working in the Family Business

In my experience mentoring next-generation successors, their biggest handicap is that they were never exposed to work in the real world.

May 23, 2023

The Advantages of Family Members Working in the Family Business

All businesses face challenges and family-owned businesses are not immune to these, but by the very nature of a family business structure, there are also unique sets of opportunities that family businesses can take advantage of.

May 31, 2023

Did You Hire Your Children Based on Talent or Birthright?

As a founder, did you consider talent or base your decision solely on birthright when you appointed family members? Was the last name of your son or daughter the sole reason? Was it purely trust? Would you have done it any other way?

June 06, 2023

Rules for Eliminating Nepotism in the Family Business

When employing people who are related to the founder, either by blood or marriage, it should always be based on the following non-negotiable metrics: outside experience, credentials, exceptional work in the past, and merit.

June 14, 2023

The Real Dangers of Nepotism in Family-Run Businesses

Why has nepotism gained more attention? The number of family businesses today is growing, and so is the awareness of the negative effects of nepotism prevalent in the context of a family business

June 21, 2023

If You Can't Avoid Nepotism, Set the Rules of Engagement

Family members in leadership positions should lead by example, demonstrating professionalism, competence, and a commitment to the success of the business

June 28, 2023

Family Before Fortune

Family Before Fortune

June 30, 2023

Family Business Covenants Against Nepotism

Regardless of blood relations, employment should never be guaranteed

July 04, 2023

Wealth Will Not Last Two Generations Part 1

"Transferring wealth to your children can be dangerous if not done thoughtfully and responsibly." - Prof. Enrique Soriano

July 18, 2023

Is Inherited Wealth Evil?

Oftentimes, children of affluent parents have not had time to establish their own identities separate from the wealth and status of the business.

July 19, 2023

A Founder's Adversity Quotient

Armed with nothing but grit, founders experience firsthand the struggles and setbacks that come with creating something from nothing, which hones them into extraordinary entrepreneurs with unmatched AQ.

July 24, 2023

Wealth Will Not Last Two Generations: The Consequences of a Low AQ

It is a fact that many next-generation family members have a Low Adversity Quotient (AQ). Consequently, when next-generation successors have low AQ, there is a significant risk that the business they inherit will suffer.

August 01, 2023

The Significance of Strategic Planning in Family-Owned Businesses

In a recent strategic planning session for a family-owned business, powerful questions emerged: 'Why are we in Business Together?' and 'Where do we want the business to be in 3 years and 5 years?'

August 09, 2023

The Dangerous Mindset of Many Next-Generation Leaders

What will it take for the next generation to break the cycle of adopting detrimental behavioral patterns and mindsets?

August 16, 2023

A Fail-Proof Succession Starts with Your Successors AQ

Often overshadowed by the larger, publicly traded corporations, family businesses operated quietly, keeping their successes and struggles within the family circle, but the landscape is changing rapidly.

August 23, 2023

From Comfort Zone to Resilience: A Next-Gen Transformative Journey

In my extensive experience helping families in Asia, the concept of Adversity Quotient (AQ) has emerged as a pivotal metric for assessing an individual's capacity to adapt and thrive in the face of adversity.

August 30, 2023

Succession Planning: The Cornerstone of Family Business Legacy and Prosperity

In family enterprises, a sobering truth prevails: With each generational transition, the odds of a company's survival diminish.

September 06, 2023

Fair Should Not Be Equal in a Family-Owned Business

Enforcing strict equality within a family-owned business can pose significant challenges, especially because family members often bring varying levels of expertise, experience, and commitment to the table.

October 12, 2023

From Family-First Leadership to Meritocracy: It's Time to Shift Part 2

His father's passing thrusts him into the role of President, a position that always seemed destined for him, but as he embarks on critical operational decisions, questions that echo through family business corridors are raised.

October 24, 2023

The Aimee and Allan Sibling Conflict, Solved! Last Part

Even siblings with harmonious childhoods can face rivalry in the professional realm due to the unique challenges a family business presents.

November 29, 2023

Founders Must Lead The Way! Part 1

In an evolving and growing family business, the key to sustained success is for the founder to recognize that the business is now a team sport, where cohesion and collaboration are paramount to winning games.

February 06, 2024

Entitled Family Members Can Undermine Business Success (Part 1)

Stewardship is the key to ensuring the long-term sustainability and success of family-owned businesses. In contrast, entitled family members can pose a significant threat to business stability.

February 20, 2024

A Hidden Crisis: 90% of Directors Are Unaware of Their Fiduciary Duties!

The intricate dynamics of familial relationships can complicate decision-making processes as they may pose a threat to the family members' commitment to their fiduciary obligations.

March 20, 2024

Upholding Non-Negotiable Values: Humility, Discipline, and Respect

As founders and mentors, we observe with deep concern the gradual erosion of humility, discipline, and respect among the next generation of leaders—a trend that threatens the very essence of our businesses.

April 03, 2024